Archive for July, 2007

By: The Scribe on July, 2007

In July 2007, workers in central Vietnam found five jars filled with thousands of Chinese coins, dating back to China’s Tang Dynasty. The coins are extremely rare and highly valuable, since they were circulated primarily in Vietnam for trade during the peak of the Tang Dynasty.

In July 2007, workers in central Vietnam found five jars filled with thousands of Chinese coins, dating back to China’s Tang Dynasty. The coins are extremely rare and highly valuable, since they were circulated primarily in Vietnam for trade during the peak of the Tang Dynasty.

Each of the coins has four Chinese characters on one side, with the opposing side left blank. Although there were a number of different kinds of coins minted during the Tang Dynasty, private casting of any coins was punishable by death, and the circulation of the various coin types was strictly monitored. Coinage alloy was highly regulated, and only certain towns were given the privilege of constructing their own minting forge.

In 718 AD, minting regulations were reaffirmed, as secret mints and forgeries began to pop up across the various townships. In 737 AD, the first official minister responsible for casting was appointed, and by the late 740s, the central government regulated that only skilled artisans could be employed to design new coinage, instead of the previously conscripted peasants.

In 808 and again in 817, a ban was applied to the hoarding of coinage, due to the sudden deterioration of value. No person, regardless of rank, was able to hold more than 5,000 strings of currency, and any balance that exceeded this amount had to be spent on the purchase of goods within two months – simply for the sake of getting more money back in circulation.

The Tang Dynasty, in general, was a period of progress and stability, so it is not unusual to see a series of coins minted specifically for trade in another location. It is likely that these were minted to ensure the value of the coinage was maintained while in another country, and it is hoped that further studies on these newfound coins will help determine exactly which part of the Tang Dynasty the coins were from – specifically before or after the ban on currency hoarding.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: A story about Regicide

By: The Scribe on July, 2007

According to forensic analysis of over 3,000 human skeletons from a collection in Croatia, dating from as early as 5,300 BC to as late as the mid-19th century, Europeans in ancient times had little to fear from the threat of cancer – in fact, it was an extremely rare disease. Analysis showed that there was a widespread variety of other infectious diseases that could prove fatal, however out of a sample of over 3,000 skeletons, only four ancient skeletons showed any signs of cancer’s telltale imprints.

According to forensic analysis of over 3,000 human skeletons from a collection in Croatia, dating from as early as 5,300 BC to as late as the mid-19th century, Europeans in ancient times had little to fear from the threat of cancer – in fact, it was an extremely rare disease. Analysis showed that there was a widespread variety of other infectious diseases that could prove fatal, however out of a sample of over 3,000 skeletons, only four ancient skeletons showed any signs of cancer’s telltale imprints.

1) Skeleton of a teenager: From a 4th-century necropolis at a former Roman colony town, tumors were found on this body’s thighbones.

2) Skull of a 50/60-year-old: From the island of Vis in the Adriatic Sea, the skull dates to the 3rd or 4th century BC and showed signs of a tumor.

3) Three or four year old child: From a Medieval cemetery near the town of Zagreb, evidence of a benign tumor was found in the bones.

4) Skeleton of a 40-year-old: From an 11th-century cemetery in Lobor, this man’s tumor was also in the thighbone.

Considering that the signs of other diseases were much more common – such as syphilis, leprosy and tuberculosis – it seems that cancer was as strange a phenomenon to ancient cultures as leprosy is to modern society.

The theory as to why this is the case simply seems to be: modern humans live longer. The average age of mortality in the bones studied from the Croatian collection was 36 years old, while the modern life expectancy in Croatia is 74 years old. Thus, it seems that the longer a person lives, the more likely it is a slow cancer will develop.

As envious as modern society may be that these ancient ancestors had little to fear when it came to cancer, the blunt truth of the matter is that something else was bound to kill them first – ending the course of their lives long before cancer ever became an issue.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Ancient Chinese secret- I mean coins.

By: The Scribe on July, 2007

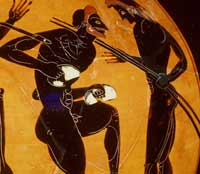

While long jumpers at the modern Olympics have the advantage of a running start before their jump, athletes in ancient Greece did things a little differently. They started their jump with both feet flat on the ground – but with a weight in each of their hands. These weights were called halteres , and their shape and size are visible on a number of vase paintings that survive from ancient Greece.

While long jumpers at the modern Olympics have the advantage of a running start before their jump, athletes in ancient Greece did things a little differently. They started their jump with both feet flat on the ground – but with a weight in each of their hands. These weights were called halteres , and their shape and size are visible on a number of vase paintings that survive from ancient Greece.

How could a heavy weight possibly help an athlete jump further? The technique was to swing both arms backward and forward before the jump, slowly gaining momentum, with the arms thrust forward at takeoff. This would allow the jumper to propel himself into the air with more force – after all, leg muscles actually become more efficient when contracting against a load. The result could be likened to a springboard effect.

With their weight shifted upward at the beginning of the jump, the athlete would then need to shift his center of mass in midair – he would thrust the halteres back behind him, and possibly even let go just before landing. This would allow his feet to push forward just a bit further, which is what counts in the long jump: where your heels land is where your distance is measured.

The weights were made out of stone or lead, and could weigh anywhere between 2 and 9 pounds, depending on the size and arm length of the athlete. They were carefully carved to provide maximum comfort when gripping the weights, and each long jumper probably had at least two sets, in case one broke when thrown back.

The weights were made out of stone or lead, and could weigh anywhere between 2 and 9 pounds, depending on the size and arm length of the athlete. They were carefully carved to provide maximum comfort when gripping the weights, and each long jumper probably had at least two sets, in case one broke when thrown back.

During the 18th Olympics in 708 BC, the role of long jumping was altered somewhat, and instead of being included as an event on its own, it was incorporated into the pentathlon. In 656 BC, although he didn’t necessarily win the entire pentathlon, a man named Chionis of Sparta earned the ancient long jump record at 7 meters and 5 centimeters – and that’s without a running start! If he had completed this jump during modern times, Chionis’ feat would have won him the long jump title at the modern Olympics in 1896, and placed in the top ten at another 8 Olympic summer games.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Ancient cancer clues

By: The Scribe on July, 2007

Although stories of paper production tend to center around its beginnings in China or Egypt, another culture developed their own system of paper production and use completely independent of these far-away societies. The Pre-Columbian Mayans made their own paper from the inner bark of fig trees – and in some cases, considered it so precious as to be sacred.

Mayan paper production started with a piece of a fig trees’ inner bark, which would be boiled and then pounded briskly with a stone, ensuring all the fibers were condensed and completely flattened. The resulting piece of bark paper was light brown with corrugated lines, and once it dried, the sheet would actually be somewhat stretchy. In addition, it was also quite delicate, and although this was bad for preservation, it meant that the paper itself was highly valued.

Amatl paper could be carefully folded or rolled up for storage, which resulted in its use as a base for many Mayan and Aztec codices, such as the Huexotinco Codex. It would be painted with a brush and then kept safe by priests or scribes working in a religious context.

On occasion, amatl paper was used for important communications between various tribes, in particular those from whom a larger tribe was demanding tribute. The paper was also used for keeping track of tribute payments and keeping other trade records, for recording books of government, and for some elite members of society who could afford to use the paper in their everyday writings.

On occasion, amatl paper was used for important communications between various tribes, in particular those from whom a larger tribe was demanding tribute. The paper was also used for keeping track of tribute payments and keeping other trade records, for recording books of government, and for some elite members of society who could afford to use the paper in their everyday writings.

In fact, it is quite likely that the use of amatl paper evolved out of the earlier Mayan bark-clothing called huun, which was made by stripping bark off a tree and beating it into shape. The Mayans would later use the bark to create small, 6 inch by 8 inch pieces of ‘paper’ for books and documents, sometimes left in strips of up to 30 feet long and then folded accordion-style. These ‘screens’ were then bound with pieces of wood or leather, decorated with jewels, and then read either like a traditional book or unrolled to its full length.

Although huun paper continued to be used until around 1000 AD, it never achieved the same prominence and sacred use as amatl. While huun tended to be used for the mundane or for the average person’s daily writings, amatl paper was treasured – a gift from the gods, not to be used lightly.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Greek long jump with weights!

Previous page | Next page

In July 2007, workers in central Vietnam found five jars filled with thousands of Chinese coins, dating back to China’s Tang Dynasty. The coins are extremely rare and highly valuable, since they were circulated primarily in Vietnam for trade during the peak of the Tang Dynasty.

In July 2007, workers in central Vietnam found five jars filled with thousands of Chinese coins, dating back to China’s Tang Dynasty. The coins are extremely rare and highly valuable, since they were circulated primarily in Vietnam for trade during the peak of the Tang Dynasty.

According to forensic analysis of over 3,000 human skeletons from a collection in

According to forensic analysis of over 3,000 human skeletons from a collection in

While long jumpers at the modern Olympics have the advantage of a running start before their jump, athletes in ancient

While long jumpers at the modern Olympics have the advantage of a running start before their jump, athletes in ancient  The

The

On occasion, amatl paper was used for important communications between various tribes, in particular those from whom a larger tribe was demanding tribute. The paper was also used for keeping track of tribute payments and keeping other trade records, for recording books of government, and for some elite members of society who could afford to use the paper in their everyday writings.

On occasion, amatl paper was used for important communications between various tribes, in particular those from whom a larger tribe was demanding tribute. The paper was also used for keeping track of tribute payments and keeping other trade records, for recording books of government, and for some elite members of society who could afford to use the paper in their everyday writings.