Archive for the ‘Ancient Egypt’ Category

By: The Scribe on November, 2007

It’s no secret that the ancient Egyptians mummified cats, monkeys, small crocodiles, even things like snakes and birds… but what about larger animals? Say, for example… a lion? Well, it turns out that not only were lions considered sacred in ancient Egypt, but the ancient records that talked about breeding and burying sacred lions weren’t exaggerating! Although no one had previously found a specimen to verify the written record, excavations from a tomb in 2001 certainly changed all that.

A mummified lion – actually one of the largest lions known to the scientific community, and obviously very old when it died in captivity – was found inside the tomb of a woman named Maia, who was the wet nurse to the famed King Tutankhamun. The nurse was buried around 1430 BC at Saqqara in northern Egypt, and was evidently held in very high regard by the royal family.

Analysis on the bones and the teeth of the lion revealed its old age, and that the lion was a captive in the royal household. The association between lions and royalty – particularly the Pharaoh – was nearly as well known as the association between kings and falcons, and plenty of Egyptologists believe that there were probably special animal precincts and sacred cemeteries at various locations in Egypt devoted to the breeding, care, and eventual buried of sacred animals such as lions.

Although none of these ‘sacred lion precincts’ have been found, the ancient Egyptians certainly had a history of setting aside specific areas for animals – for example, the city of Crocodilopolis was specifically devoted to crocodiles and contained a sacred pond for the animals.

The lion inside the Saqqara tomb was found stretched out on a rock, with the body oriented eastward and the head pointing north. Most of the wrappings had been lost, but the positioning and the surrounding context revealed its mummification had been complete at the time of burial – and in terms of the scientific community, the bones represent those of the largest male lion to ever be recorded.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Giant Scorpions!

By: The Scribe on November, 2007

The mummy of a child from ancient Egypt caused scientists to do a bit of a double-take when they performed a CT scan on the body – images revealed that a spear-like object was wedged inside the child’s skull and upper spine!

CT scans are commonly performed on mummies so that not all bodies need to be unwrapped for study – in many cases, the mummies are so fragile that unwrapping them might potentially destroy the remains. Instead, X-rays on the body reveal things like how a person was wrapped and buried, the condition of the skeleton, and whether there are any added items inside the wrappings such as jewelry or ornamentation.

The child with a spear in its head was probably between three and five years old when it was buried, and the scan seemed to show that the child had an unusually large head. While scientists haven’t been able to pinpoint the cause of the abnormality, the bone structure of the head and face may result in a facial recreation sometime over the next several years.

However, the primary question still remains – was the spear in the child’s head a cause of death, or did the embalmers insert the spear in order to keep the head and neck steady during the mummification process. Either explanation is entirely plausible, though the former explanation is far more disturbing to consider.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Pre-History’s Next Top Model

By: The Scribe on November, 2007

In 2007, Archaeology magazine reported that a team digging at the ancient Egyptian city of Hierakonpolis – about 400 miles south of Cairo – had discovered something in the site’s ‘elite cemetery’ that validated the city’s role in the development of the Egyptian state around the time of the First Dynasty.

The name Hierakonpolis translates as “the city of the falcon”, and what was found there was the earliest depiction of a falcon ever discovered – something which meant a lot to the Egyptian people throughout the Dynastic period. However, before that in the Predynastic period, the falcon was one of the clearest surviving examples of a symbolic image or motif that would carry on from those early centuries into the Dynastic period.

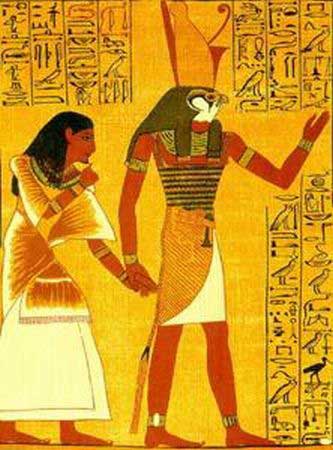

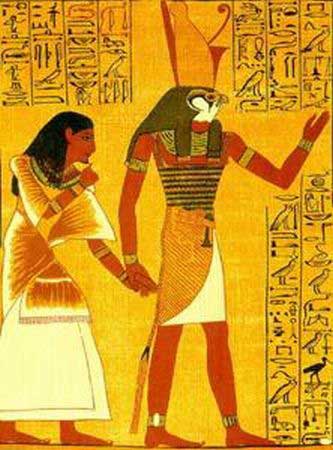

Once the Dynastic period arrived in Egypt, the image of a falcon symbolized the king or Pharaoh, who was supposed to represent the embodiment of the god Horus – the falcon-headed deity of Egyptian religion. Horus was the patron god of kingship, and therefore the discovery of this falcon-shaped figurine at Hierakonpolis actually pushes back the association of falcons with royalty to nearly half a millennium earlier than previously thought.

The team that found the figurine was headed by archaeologist Renee Friedman, and the piece was actually located inside of one of the city’s structures that surrounded the largest known early Predynastic tomb in Egypt. Unique finds weren’t unusual for this tomb – previously, the tomb yielded an ivory carving of several hippos as well as a buried African elephant – suggesting that whoever was buried in the tomb was extremely important, and likely a very powerful ruler. With the discovery of a falcon carving, due to its association with royalty, there can be little doubt that it was a very important king who owned this tomb.

The falcon figurine is about 2.4 inches large, measuring from the tip to its tail, and appears to have been the work of a very skilled craftsman – and while the profile and shape of the figurine are similar to later falcon representations, the major difference is that the wings for this piece were carved free from the body and left attached only by a small, singular point. The falcon was carved out of a piece of malachite-veined basalt, which is what gives it the multi-colored appearance.

The city of Hierakonpolis may be familiar to some as the home of the legendary king Narmer, who Egyptologists used to credit as the founding father of Egypt – he was cited as the man who single-handedly unified the entire country and established the First Dynasty around 3100 BC. However, the discovery of a falcon figurine here in association with a royal burial – and according to the excavators, a number of other ‘falcon wings’ were found in the same area, though they had originally been mistaken for ears from human sculptures – presents some fairly compelling evidence for the leading role of Hierakonpolis in the birth of the Egyptian state, which apparently took much longer to develop than anyone had previously suspected.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Wall Paintings at an Ancient Peruvian Fire Temple

By: The Scribe on October, 2007

Ever wonder how the Egyptians managed to build their large monuments, let alone get them where they needed to be? After all, even if the shapes of statues were carved out once the stone was in place, the stone needed to get to its destination somehow – and there weren’t simply giant limestone stores in the city, either. People had to quarry the stone that to be used, and then transport it to the site where the temple or monument was being built – sometimes hundreds of miles away.

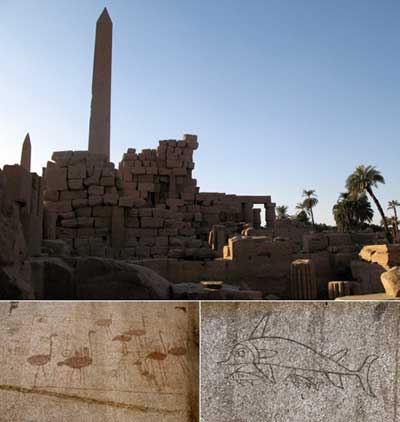

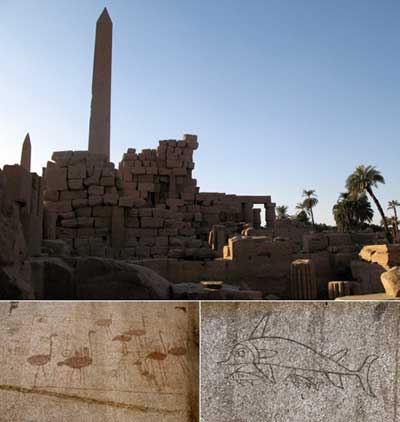

The standing suspicion was that the Egyptians moved their massive stone artifacts from one place to another via waterways – there are plenty of paintings and carvings from Egyptian tombs that show people using large boats and barges to move things like statues and obelisks, and it is not hard to see that both the Luxor Temple and the pyramids at Giza have ancient canals that lead up to their “front door”, as it were.

The only problem was, nearly all the known obelisks from ancient Egypt came from a granite quarry in Aswan – and until now, there was no known canal route to get them from the quarry all the way up the Nile to other cities, except by dragging the monument across the ground on a land journey. That clearly would not have been an ideal situation for these artifacts, considering that some of the larger obelisks can weight upwards of 50 tons. One of the unfinished obelisks in the Aswan quarry is estimated at over 1,100 tons – and was abandoned by the ancient workers only because of the appearance of latent cracks, and not because of its weight.

However, recent discoveries have revealed that there may have been a canal in Aswan after all, hidden from historians for centuries by modern roadwork. This canal would have made transporting obelisks a nearly effortless endeavor, as compared to moving them by land: the canal linked the Aswan quarry with the Nile, which meant that the obelisks could have been moved from the quarry to the Nile, and then sailed down the Nile to their final destination.

The only downside to this method was that the timing had to be perfect – in ancient Egypt, the Nile flooded several times annually, and it was the floodwater that would have filled up the quarry’s canal. So, in order to take advantage of the floodwaters and actually use the canal, workers would have needed to finish their obelisks on time, move the monuments onto rafts and into the canal at a point below the floodwater levels, and wait for the water to come – then the monuments could easily float once the flood came.

As a side-note, the archaeologists who found the Aswan quarry also discovered graffiti drawings left behind by quarry workers thousands of years ago, as well as grid markings that would have helped with measurements for the obelisks. Some of the graffiti includes images of ostriches and dolphins, but as water levels rise in the area, Egyptologists fear that the graffiti will be lost or washed away forever.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: What the Hellespont are ‘the Dardanelles’?

Previous page | Next page