Archive for the ‘Ancient Egypt’ Category

By: The Scribe on October, 2007

The fort of Tjaru, also called Tharo, was an ancient Egyptian fortress along the major road from Egypt to Canaan. Known as ‘the way of Horus’, the road was extremely important for both travel and trade – and in times of war, whoever controlled the road essentially controlled the territory. Previously known only through descriptions and images, archaeologists have finally uncovered the fort itself – and it turns out that this fort was one of the largest fortresses to have existed during the Pharonic era in ancient Egypt.

The walls of the fort were made with mud brick and were 13 meters thick! Twenty-four watchtowers were built above the parapets on the walls, and a deep moat was dug around the entire perimeter of the city – and this was only one fortress in a chain of 11 that spanned all the way from the Suez to the current Egyptian-Palestinian border.

Inside the fortress, workers discovered graves containing horses and soldiers buried together, attesting to the severity of the battles in this area during the Egyptian struggle against invaders known as the Hyksos. In the 17th century BC, the Hyksos had invaded Egypt and eventually took control of the country, ruling the entire Nile during a time known as the “Second Intermediate Period”. They managed to hold the country for approximately 100 years before the Egyptians took back control of their land – and in order to secure themselves against future Hyksos invasions, giant fortresses were built along the river.

Although clear evidence of this specific fortress had not been found until now, a depiction of Tjaru could be seen on the walls of Karnak Temple in Luxor – depicting everything from the moat around the fortress to the large, wooden beams that spanned areas of its construction. Tjaru was also mentioned under the name ‘Silu’ in one of the Amarna letters, which were a series of correspondences between the Egyptian rulers and their representatives – ie. diplomats – residing in Canaan during the 15th century BC.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: More Ancient Standard

By: The Scribe on October, 2007

Before Alexander the Great made his way to the Nile delta and established his own city in 331 B.C., the northern coast of Egypt was home to a city called Rhakotis. Although Rhakotis is mentioned in several ancient history texts, until recently, the actual existence of the city had never been proven – but now, it seems as though Alexander the Great was more of a renovator than a city builder.

Teams of underwater archaeologists were diving in Alexandria’s bay, searching for Greek and Roman ruins, when they stumbled across some signs of building construction that appeared to be 700 years older than Alexander the Great’s arrival in the area. In order to substantiate the evidence, researchers took soil sample cores from the Mediterranean ocean’s floor – some as large as 20 feet long – and dated them with radiocarbon technology.

The cores revealed that the ocean floor held lead and human waste that was over 3,000 years old, confirming that there was indeed human habitation along these shores long before Alexander ever arrived; the cores also contained pieces of stone building materials that would have come from southern and central Egypt. By looking at historical documents that have survived the centuries, all evidence pointed to the true, historic existence of the Egyptian city of Rhakotis.

The lead from the cores was dated to around 1000 to 800 BC, with some portions suspected to date back even further to Egypt’s Old Kingdom – if this is true, it means that people were living here over 2000 years before Alexander arrived! Lead was a very important substance for humans in the ancient world, and in large cities, it was not unusual for lead to be used in everything from fishing, building, ship construction, and plumbing, to more artistic activities like glass making.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Urban conflict in Ancient Syria

By: The Scribe on October, 2007

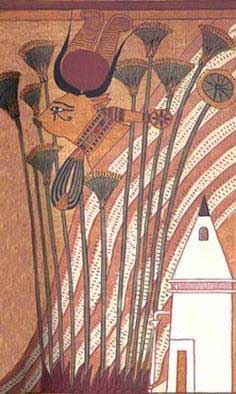

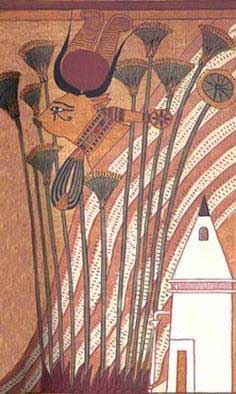

The Eye of Horus is a symbol from ancient Egypt, typically associated with protection and royal power from the Egyptian deities Ra and Horus. The Egyptian word for the symbol was ‘wadjet’, which sprung from its early associations with one of Egypt’s earliest deities, Wadjet. Over time, Wadjet the goddess was assimilated into the personas of other Egyptian goddesses, including Hathor, Bast, and Mut.

The Eye of Horus is a symbol from ancient Egypt, typically associated with protection and royal power from the Egyptian deities Ra and Horus. The Egyptian word for the symbol was ‘wadjet’, which sprung from its early associations with one of Egypt’s earliest deities, Wadjet. Over time, Wadjet the goddess was assimilated into the personas of other Egyptian goddesses, including Hathor, Bast, and Mut.

As Wadjet’s symbol, the Eye was said to see everything – which may be where the first concept of a supernatural ‘all-seeing eye’ arose – however, as Wadjet’s importance in the Egyptian pantheon diminished, the Eye began to be frequently represented as a trait of the goddess Hathor.

In Egyptian mythology, Hathor was the wife of the god Ra, and became the mother of the god Horus. As the story goes, one of Horus’ eyes was damaged when he fought with his uncle Set, who had murdered the god Osiris and tried to seize the Egyptian throne. As a result, Horus’ eye, its injury, and eventual restoration caused the Eye of Horus symbol to become an important image in representing the concept of renewal and rebirth after death.

Horus himself was an Egyptian sky god, depicted most often as a falcon. The Eye of Horus is thus shaped much like a peregrine falcon’s eye and markings, including a ‘teardrop’ mark that is often found under the bird’s eye. Since the ancient Egyptians believed that the Eye of Horus was powerful enough to assist an individual in his rebirth after death, amulets and images of the Eye were often included in burial wrappings – in fact, an Eye of Horus was found under the twelfth layer of wrappings on the mummy of King Tutankhamun.

In ancient Egyptian mathematics during the Old Kingdom, the Eye of Horus could also represent a rounded off number one, but would later shift in meaning as the Egyptians developed a higher understanding of complex math.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: A 1000-year-old Viking treasure trove

By: The Scribe on September, 2007

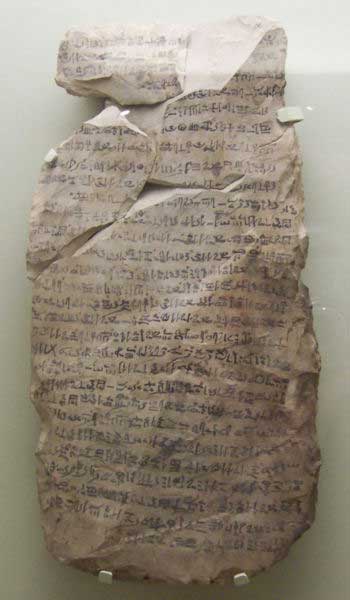

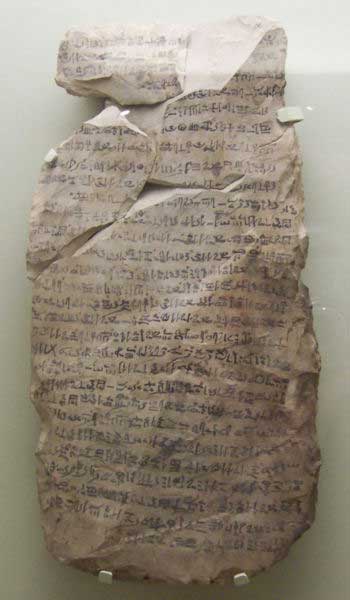

For anyone who is even vaguely familiar with Egyptian hieroglyphs, it’s fairly clear to see that the writing process in ancient Egypt was a little more laborious and involved than the effort it takes to write down words today using the Latin alphabet. In fact, writing with hieroglyphs was such a time-consuming process that even the ancient Egyptians got tired of how long it took to get a short note down… and much in the same way that a person today might take notes using standard shorthand notation, ancient Egypt had its own “short-hand” form of hieroglyphs! This was known as the hieratic script.

The hieratic writing system was developed alongside the hieroglyphic system, essentially for the purpose of allowing scribes to write information down quickly, without resorting to the laborious process of writing and drawing hieroglyphs. It is important to note, however, that hieratic is not a derivative of hieroglyphic writing – they were simply scripts developed in parallel, each for their own specific purpose.

The earliest appearance of hieratic came around 3200 BC, and was used for a variety of purposes: legal texts, personal letters, administrative documents, historical accounts, literary writings, medical texts, mathematical theorem, and also religious documents. In fact, when the usage of the more popularly known hieroglyphs and the lesser known hieratic scripts are compared – it isn’t hard to see that hieratic was actually a far more important type of writing than hieroglyphs, since hieratic was used on a daily basis for everyday living.

Hieratic was also the first writing system that students would learn when they entered into an educational program in ancient Egypt, and there are plenty of surviving examples of students’ practice texts from thousands of years ago. It was typically written with ink and a reed brush onto papyrus, stone, wood, or shards of ostraca. On occasion, hieratic would be used to write a religious text onto the linens of someone being mummified.

Unlike hieroglyphs, hieratic was always written from right to left in horizontal lines, both so that the scribe’s hand would not smudge what he had just written, as well as to increase writing speed. However, even with the hieratic serving as a shorthand form of writing, there were two variations on the script – a relaxed, businesslike form that was used for administrative documents, and an uncial bookhand-form that was used for more important literary, religious, or scientific texts. Comparatively, it would be like English writers using cursive writing for important documents, and using printed letters for everything else.

In addition, personal letters had their own form of shorthand hieratic, using a highly cursive and stylized version of the script – in these texts, there are plenty of abbreviated words and phrases, which is not unusual to find in any modern language today! By 200 AD, hieratic had been demoted to use primarily for religious texts, with a new non-hieroglyphic form of writing called demotic taking its place.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: A (French) Pirate of the Caribbean

Previous page | Next page

The

The