Archive for the ‘Ancient Egypt’ Category

By: The Scribe on September, 2007

As they excavated a burial chamber in Luxor, the group of archaeologists who worked there hoped with all their might that they would discover a new mummy inside this tomb. When they finally made it inside the chamber, they found seven coffins, which they hoped would contain the carefully wrapped mummies of Egypt’s royal queens, or perhaps even the mother of Tutankhamun himself!

As they excavated a burial chamber in Luxor, the group of archaeologists who worked there hoped with all their might that they would discover a new mummy inside this tomb. When they finally made it inside the chamber, they found seven coffins, which they hoped would contain the carefully wrapped mummies of Egypt’s royal queens, or perhaps even the mother of Tutankhamun himself!

In a public display that seems to characterize today’s Egyptian finds, both researchers and local/international media were invited to watch the opening of the last coffin as it sat in its chamber, only a few steps away from Tutankhamun’s own ancient tomb. With bated breath, the archaeologists opened the final coffin, and found… flowers?

Indeed, instead of simply finding a body wrapped in its burial shroud, the coffin contained a perfectly preserved garland of flowers, estimated to be at least 3,000 years old. According to some of the team who had worked on excavating the tomb, the find was better than a mummy – after all, there is absolutely nothing like it in any museum in the world.

While there are plenty of drawings of flowers on Egyptian artifacts and documents, nothing like the garland has ever been found, not to mention that no one had ever even considered something so fragile would survive for three thousand years. Looking back at Egyptian art, it isn’t too difficult to see that there are many images of members of the Egyptian royal family wearing garlands of flowers, many of which were entwined with strips of gold, around their shoulders – and that they wore these golden garlands both in life and death.

At only five meters away from the tomb of Tutankhamun, there are still plenty of theories as to whom it was that this new tomb belonged. However for now, this ancient flowery necklace is enough to keep researchers busy, as they continue to draw links between what was depicted in Egyptian art and the Egyptians’ real-life ancient practices.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Ancient beehives

By: The Scribe on August, 2007

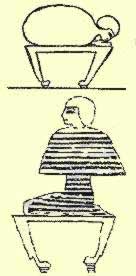

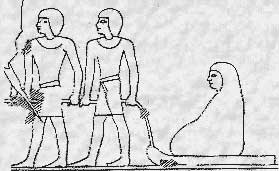

Appearing most often in burial scenes, the tekenu was a mysterious figure that shows up on tomb paintings and funerary texts – though who he is or why he appears remains unknown. The tekenu seems to be the figure or shape of a man, and is shrouded in either a bag, animal hides, or a sack that is placed on its own sledge in the midst of a funeral procession.

Appearing most often in burial scenes, the tekenu was a mysterious figure that shows up on tomb paintings and funerary texts – though who he is or why he appears remains unknown. The tekenu seems to be the figure or shape of a man, and is shrouded in either a bag, animal hides, or a sack that is placed on its own sledge in the midst of a funeral procession.

One theory suggests that this shrouded figure was actually a sack of spare body parts left over from the mummification process, since it was pulled alongside the canopic jars and sarcophagus containing the mummified corpse. If this is the case, the images of the tekenu where he has a face must mean that there was a mask or a false head placed at the “neck” of the sack, causing the tekenu to appear as if it was a real person. It may have also simply served as an image of the deceased individual himself.

Other suggestions have been made that try to link the tekenu to possible human sacrifice in ancient Egyptian history. One oft-cited piece of evidence for this comes from an inscription found on the Tomb of Rekhmire, which reads: “Causing to come to the god Re as a resting tekenu to calm the lake of Khepri.” The thought is that this may be a remnant from a time when humans were killed and thrown into a lake to appease certain gods – however, there is no additional evidence for this, nor for the tekenu ever having been a human sacrifice.

Other suggestions have been made that try to link the tekenu to possible human sacrifice in ancient Egyptian history. One oft-cited piece of evidence for this comes from an inscription found on the Tomb of Rekhmire, which reads: “Causing to come to the god Re as a resting tekenu to calm the lake of Khepri.” The thought is that this may be a remnant from a time when humans were killed and thrown into a lake to appease certain gods – however, there is no additional evidence for this, nor for the tekenu ever having been a human sacrifice.

In fact, in the Tomb of Mentuherkhepshef (try saying that five times fast) from the 18th dynasty, there is a man lying on a sledge, just like the tekenu, but unshrouded. In another scene from the Tomb of Rekhmire, the tekenu is removed from his sledge and placed on a chair inside a tomb, placed with its head poking out of the bag. In the scene following this, the same man is sitting upright on the chair, wearing a shroud wrap but also clearly supposed to be alive.

Egyptologist Greg Reeder has interpreted this series of images as finally revealing who and what the tekenu was. Reeder’s theory is that this was a Sem priest who initially went into a trance at the beginning of the funeral procession, playing the role of a shaman who “visited the deceased in the otherworld… as the tekenu he is transported to the tomb wrapped in a shroud to help facilitate his ‘death’ so that he can be transported to the other world”.*

The priest’s visit to the spirit world was supposed to give him powers that subsequently enabled him to perform the traditional ‘Opening of the Mouth’ ceremony that was held during all burial rituals. Essentially, the role of tekenu was then to go through a state of metamorphosis from the tekenu to Sem – a transition from death to life.

Of course, there are currently no other texts that might support this interpretation… but this is the most plausible theory thus far.

*Greg Reeder, “A Rite of Passage: The Enigmatic Tekenu in Ancient Egyptian Funerary Ritual”, KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt 5 (1994).

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: More great Ancient Standard

By: The Scribe on August, 2007

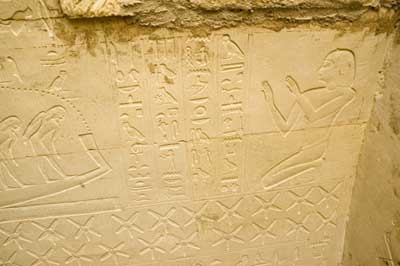

A necropolis just south of Cairo, once used for burials by Egypt’s royal family in the 5th dynasty, was apparently selected for an extreme makeover courtesy of the nobles of the 26th dynasty, after it had fallen into disrepair. Never mind that the burial grounds were 2,000 years old – why build a bunch of new chambers when these ones would work just fine with a fresh coat of inscriptions?

The 5th dynasty’s reign was rather minimal to begin with, spanning only the period between 2498 and 2345 BC. At this time, Egypt’s capital was the city of Memphis, although it was shortly put into disuse when the next dynasty of nobles came into power. Twenty centuries afterward, the royal family of the 26th dynasty wanted to be buried near the temples of Saqqara – which is fairly close to Memphis – and this seemed like the perfect place to do it!

So, the burial chambers at the necropolis were recycled for the 26th dynasty’s own purposes – and what they did to the place has been described as “gentrification”, which means that they fixed it up to look excessively refined and elegant. One of the most interesting recycled burial chambers at the site was actually that of a royal scribe, named Menekhibnekau, who lived during the 5th dynasty.

The chamber is about 20 meters underground, and the shaft entrance seems to have been inspired by the nearby step-pyramid at Saqqara. Inside the burial chamber itself, there was a vaulted ceiling, completely covered with stars for decoration. There were also two large sarcophagi: one that appeared to be an exterior coffin, made from limestone, while the other was human-shaped and was made out of dark green sandstone called greywacke. Both sarcophagi were also thoroughly covered with religious texts.

Excavators of this burial chamber could easily tell it had an extreme makeover, due to the vastly different style of decoration on the walls of the chamber. The south side was decorated with a chapter of text from the Book of the Dead and images of guardsmen, while the east and western sides had pictures of figures that represented Time, alongside a solar barque and additional sacred texts.

Although this chamber is one of few that can conclusively be said was redecorated, there are many more burial chambers at the necropolis that have yet to be examined – hopefully these will provide another look into just how extensive the redecoration project was!

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Brits have always liked French fashion

By: The Scribe on August, 2007

In the entire history of ancient Egypt, it’s a wonder that there aren’t more inscriptions or tomb paintings that depict the inevitable neck pain that must have ensued as a result of the use of Egyptian pillows. As seen in the image above, the ancient Egyptians did not use a pillow to sleep on each night so much as a headrest – and one that was uncomfortably high, no less.

Egyptian headrests were used each night to support the head while a person was asleep, and consisted of a curved upper section to cup the head on top, with one or two pillars leading downward to a flat base. These “pillows” could be made from a variety of materials, including ivory, marble, stone, ceramic or wood. There is some debate over whether or not a small cushion was placed in the curving part to make the headrest more comfortable, however there is no artistic nor written evidence thus far to support this idea.

Regardless of comfort, pillows were important both to the living and the deceased, since the ancient Egyptians tended to view death as an eternal kind of sleep – as a result, many of the headrests found in Egyptian tombs were inscribed with the owner’s name and epithets.

Another interesting feature of Egyptian headrests is that they were not only practical to get a good night’s sleep (regardless of how uncomfortable it might look to modern eyes), but they also had a religious association with the solar cult – one’s head was lowered at night and rose in the morning, just like the sun. A headrest from the tomb of King Tutankhamun illustrates this association: the base of the headrest is made up of two “lions of the horizon”, while the god Shu holds up the head’s cup, in the same manner as is seen in the Book of the Dead where the solar barque rests on a stand.

The only indication of something potentially more comfortable being used to support the head was an unusual artifact found in April 2006. It was a 4,000-year-old pillow that was made out of woven plant fibers encased in a wax coating – leading toward some speculation that perhaps some finicky Egyptian nobles eschewed the harder headrests in favor of softer comforts. Of course, this also reopened the debate over whether pillows like this were once placed overtop headrests to make things more comfortable, with all the other organic pillows simply degrading over time, leaving just the headrests for archaeologists to find.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: A Brief History of the German Language

Previous page | Next page

As they excavated a burial chamber in Luxor, the group of archaeologists who worked there hoped with all their might that they would discover a new mummy inside this tomb. When they finally made it inside the chamber, they found seven coffins, which they hoped would contain the carefully wrapped mummies of Egypt’s royal queens, or perhaps even the mother of Tutankhamun himself!

As they excavated a burial chamber in Luxor, the group of archaeologists who worked there hoped with all their might that they would discover a new mummy inside this tomb. When they finally made it inside the chamber, they found seven coffins, which they hoped would contain the carefully wrapped mummies of Egypt’s royal queens, or perhaps even the mother of Tutankhamun himself!

Appearing most often in burial scenes, the

Appearing most often in burial scenes, the  Other

Other