Archive for the ‘Ancient Egypt’ Category

By: The Scribe on August, 2007

Found on the foot of an ancient Egyptian mummy, it appears that a false toe commonly referred to as the “Cairo toe” may have been more than purely decorative – in fact, it may have been the world’s first functional replacement body part! The worn-down false toe was found fastened onto the mummified foot of a middle-aged woman, and it appears that the amputation site of her large toe had healed perfectly during her lifetime – probably allowing her to wear a false toe with some level of comfort, and thus enabling her to walk properly again.

Found on the foot of an ancient Egyptian mummy, it appears that a false toe commonly referred to as the “Cairo toe” may have been more than purely decorative – in fact, it may have been the world’s first functional replacement body part! The worn-down false toe was found fastened onto the mummified foot of a middle-aged woman, and it appears that the amputation site of her large toe had healed perfectly during her lifetime – probably allowing her to wear a false toe with some level of comfort, and thus enabling her to walk properly again.

The toe is similar to another ancient Egyptian false toe from the British Museum, which is why both toes were previously thought to have just been cosmetic additions for the wearer without any additional benefits. However, it was recently noticed that the toe from Cairo shows signs of wear and also bends in three places – exactly the same way as any other human’s large toe works.

Alternately, the fake toe from the British Museum does not bend, and was made out of the less durable material called cartonnage, which is a kind of papier-mache made from linen, plaster, and glue. While it also shows signs of wear, suggesting that it was worn during the owner’s lifetime, the fact that it does not bend seems to imply it was used for the sake of appearances only and did not help the wearer to walk correctly.

Tests are planned to determine whether either one of these false digits could actually help someone who was missing their large toe to walk unhindered – if the tests are successful, it will mean that the Cairo toe is officially the world’s oldest artificial body part, beating out a hollow bronze leg from Rome by over a thousand years!

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Ancient identity theft!

By: The Scribe on July, 2007

The city of Crocodilopolis was located on the western bank of the Nile, southwest of Memphis in Egypt. Known to the ancient Egyptians by the somewhat less redundant name of Shedet, this city was the center of worship for the Egyptian god Sobek, the (you guessed it) crocodile god. Ever the subtle geniuses when it came to naming foreign places, the ancient Greeks dubbed it “Crocodile City”, or “Crocodilopolis”, as it is now remembered.

Inhabitants of Crocodilopolis worshiped a manifestation of Sobek through a sacred crocodile kept at the city, named ‘Petsuchos’ – a name that means “son of Sobek”. The crocodile was adorned with gold and jewels, and was kept in a temple with its own pond, sand, and special priests to serve his food. After the residing Petsuchos died, the body would be mummified and given a special burial – and then promptly replaced with another “son of Sobek”.

Crocodilopolis never became a large city, nor developed any major political standing in the area, and in the 3rd century BC the city passed into the hands of the Ptolemies. It was renamed Ptolemais Euergetis for awhile, but was renamed again to Arsinoe only a short time later by Ptolemy Philadephus II to honor his sister and wife, Arsinoe II.

On the plus side, Crocodilopolis was located in the most fertile region in Egypt – part of the current-day Fayum – which meant that the city was a haven for farmers growing corn, vegetables, flowers, and olives. Currently, what remains of Crocodilopolis is quite minimal – there are several mounds of ruins, and a few column bases here and there, but not much has been left behind by the sands of time. There is a modern city near the ancient site, however the modern inhabitants seem to have decided against penning up a crocodile inside the church.

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Disappearing Ocean!

By: The Scribe on June, 2007

*Note of Forewarning: This article deals with the topic of ancient sexuality, and may not be suitable for younger eyes.

One of the earliest gods of the ancient Egyptian pantheon was a god named Min, originally identified with Horus during the Predynastic period. First called the “Chief of Heaven” and associated with the sky, it was not long until Min became the primary fertility god of ancient Egypt.

In Egyptian art, Min was depicted wearing a tall feather crown, holding a flail in his right hand, and in his left hand… well, that’s where things start to get a bit awkward. Min is what can be called an ‘ithyphallic’ god, which means that he is shown in artwork with an uncovered and erect phallus – however, it should be noted that this kind of imagery was not necessarily seen as a sexual image by the Egyptians. Instead, it was a normal way of showing Min’s role as an agent of fertility.

In his role as a fertility god, Min was in charge of the rain, and each year at the beginning of the harvest season, there was a “Festival of the Departure of Min” – his statue would be taken out of his temple and brought into the fields, where participants would sing praises to Min and play games in the nude, hoping this would cause him to bless their harvest with his favor.

Playing games in the nude was not really a big deal to the ancient Egyptians – after all, in their hot and humid climate, serving women, dancers, and even farmers would work in the nude. Children typically didn’t even wear clothing at all until their official coming of age ceremonies.

Where things get a bit awkward for modern historians, however, is in the discussion of Min’s symbols. All the ancient gods had their own symbols, since religion was such an integral part of daily life in ancient Egyptian culture. Min’s symbols were mostly typical of a fertility god: a white bull, a barbed arrow, and… lettuce?

Where things get a bit awkward for modern historians, however, is in the discussion of Min’s symbols. All the ancient gods had their own symbols, since religion was such an integral part of daily life in ancient Egyptian culture. Min’s symbols were mostly typical of a fertility god: a white bull, a barbed arrow, and… lettuce?

Lettuce, an item not usually associated with fertility, was apparently a favorite food of Min. Why? According to the ancient Egyptian texts, this particular variety of lettuce was considered to be an aphrodisiac – and not only that, but this lettuce plant was tall, straight, and when pressed… it produced a white, milky sap substance that was, of course, easily associated with another male bodily fluid.

In fact, ancient Egyptians considered a lot of things to be aphrodisiacs… some varieties of onion were forbidden to celibate priests, in fear that they might desecrate themselves if they took a bite! Regardless, Min was an extremely important ancient Egyptian god, and well respected among the people. Although seeing a depiction of a man holding himself on the side of a building or as a public statue would have a completely different meaning today, to the Egyptians, this was perfectly normal and acceptable. In fact, if Min and his phallus weren’t around – they might not have anything to eat next harvest season.

Tomorrow: Tasty jelling stones!

By: The Scribe on June, 2007

According to some finds from the tomb of King Tutankhamun, the boy king greatly enjoyed a wee nip of red wine now and again…

According to some finds from the tomb of King Tutankhamun, the boy king greatly enjoyed a wee nip of red wine now and again…

Wine was actually a luxury item in ancient Egypt, with beer and mead being much more popular alcoholic beverages among the masses. And naturally, if the King enjoyed wine while he was alive, he was going to need something to drink in the afterlife! Although the containers for wine were readily identified from the tomb, the color and makeup of the wine was not known until scientists were able to carry out chemical analysis on the compounds left behind inside the containers.

It turns out that these wine pitchers had an acid residue inside, which Spanish scientists were able to identify as a substance typically left behind by red wine after it has dried up. In the extremely dry and sealed environment of King Tut’s tomb, the acid did not disintegrate or break down as it otherwise may have in a humid environment. Scientists took scrapings from the inside of the pitchers, and used techniques known as ‘liquid chromatography’ and ‘mass spectrometry’ to reveal the syringic acid left behind when a compound found in red wine called malvidin breaks down.

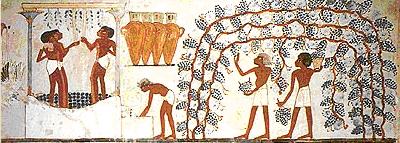

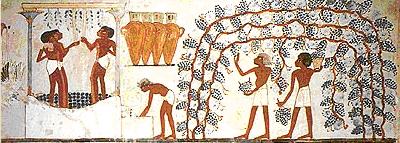

Tomb paintings have caused speculation for decades over whether ancient Egyptians drank red wine, since many of the wine-making images showed red or purple grapes being pressed, though until now there was no definitive proof for its production.

Much like today’s wine-bottles, the pitchers found in King Tutankhamun’s tomb also contained labels on the front, identifying the name of the wine, its year of production and harvest, the source of the wine, and even who grew the grapevines! For example, one jar held the label: “Year 5, Wine of the House-of-Tutankhamun Ruler-of-the-Southern-on, l.p.h. in the Western River. By the chief Vinter Khaa”.

In addition, these same techniques were used on some other containers from the tomb, allowing scientists to discover that the ancient drink Shedeh, once considered the most precious and sacred drink in Egypt, was made from grapes and not pomegranates, as it had previously been thought!

Want to read more?

Tomorrow: Welcome to the cave man art show!

Previous page | Next page

Found on the foot of an ancient Egyptian mummy, it appears that a false toe commonly referred to as the “Cairo toe” may have been more than purely decorative – in fact, it may have been the world’s first functional replacement body part! The worn-down false toe was found fastened onto the mummified foot of a middle-aged woman, and it appears that the amputation site of her large toe had healed perfectly during her lifetime – probably allowing her to wear a false toe with some level of comfort, and thus enabling her to walk properly again.

Found on the foot of an ancient Egyptian mummy, it appears that a false toe commonly referred to as the “Cairo toe” may have been more than purely decorative – in fact, it may have been the world’s first functional replacement body part! The worn-down false toe was found fastened onto the mummified foot of a middle-aged woman, and it appears that the amputation site of her large toe had healed perfectly during her lifetime – probably allowing her to wear a false toe with some level of comfort, and thus enabling her to walk properly again.

Where things get a bit awkward for modern historians, however, is in the discussion of Min’s symbols. All the ancient gods had their own symbols, since religion was such an integral part of

Where things get a bit awkward for modern historians, however, is in the discussion of Min’s symbols. All the ancient gods had their own symbols, since religion was such an integral part of  According to some finds from the tomb of King Tutankhamun, the boy king greatly enjoyed a wee nip of

According to some finds from the tomb of King Tutankhamun, the boy king greatly enjoyed a wee nip of